How a Laterally Zoned Batholith is Formed

The southwestern margin of North America (NA) is includes thick Jurassic and Cretaceous volcanic sequences and numerous cogenetic plutonics that are typically mafic and yield primitive geochemical (isotopic) compositions. These igneous assemblages have long-been interpreted as products of intra-oceanic arcs that were sutured to NA. Several tectonic models suggest that this chain of arc rocks was one continuous island arc, the so-called Guerrero Superterrane, which collided contemporaneously during the Late Cretaceous along its length from southern California to southern Mexico. This interpretation is in direct contradiction with the observations from numerous geochemical, geochronological, structural, and geophysical studies that highlight dramatic along-strike variations in the belt.

We argue that the proposed Guerrero Superterrane is composed of at least three distinct segments ( Santiago Peak, Alisitos, and Guerrero) with a major Early Cretaceous oblique slip structure juxtaposing the Santiago Peak and Alisitos segments and infer that a similar structure must juxtapose the Alisitos with the Guerrero. The Early Cretaceous Santiago Peak arc, from the Transverse Ranges in southern California to the ancestral Agua Blanca fault (aABF) in Baja California, developed subarially atop a Late Triassic-Jurassic NA accretionary prism. South of the aABF to at least the 30th parallel the Alisitos arc developed in a submarine environment on oceanic lithosphere seemingly isolated from continental influences until just prior to its accretion to NA. Accretion was accommodated along the aABF and Main Mártir Thrust, both major southwest-vergent ductile shear zones. South of the 27th parallel in mainland Mexico others have determined that the Guerrero segment is composed of multiple sub-segments each inferred to represent a distinct arc. However, each sub-segment has been shown to be built upon continentally-derived clastic sediments with an inferred NA. provenance. Thus, the entire Guerrero segment likely developed adjacent to the continent on distal slope basins and old accretionary prisms. In this view the east-vergent thrust faults common throughout the Guerrero segment likely accommodated the telescoping of a broad continental margin arc during the Late Cretaceous and not suturing.

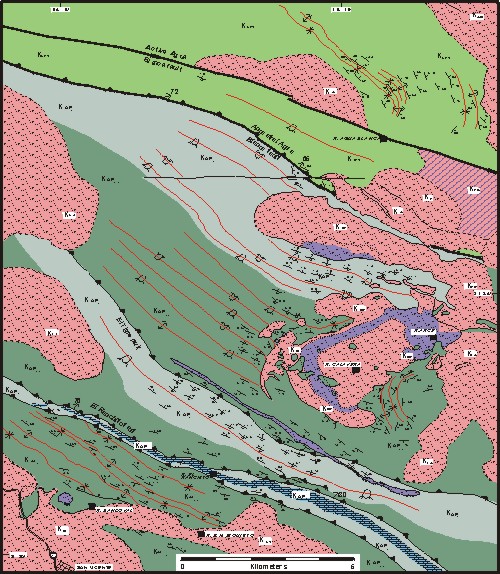

Map of southwestern North America showing the various tectonic elements with those most important to the Mesozoic evolution of the Peninsular Ranges labeled with arrows. (Map by Helge Alsleben, after Gastil, 1993)

The Santiago Peak arc:

A unique continental margin arc

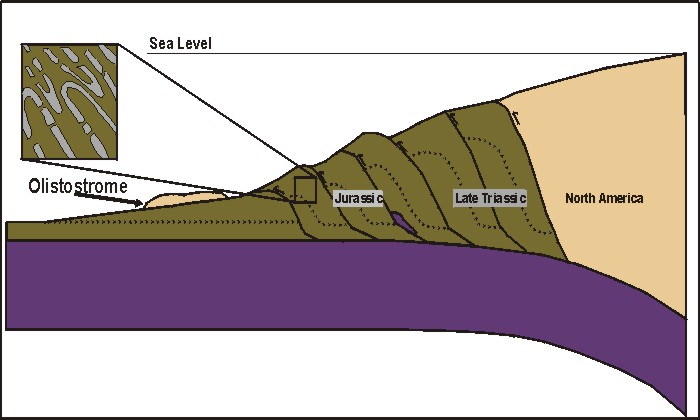

The basement of the Santiago Peak Volcanics is composed of continentally derived turbidite sequences. Descriptions of the turbidite sequences of the central zone north of the Agua Blanca fault reveal consistent features throughout the northwestern Peninsular Ranges. These include similar lithologies and inferred depositional environment, style and magnitude of deformation, presence of olistoliths, detrital zircon populations that indicate a source that included Precambrian to Triassic exposures, and a general depositional age that ranges between Late Triassic and Jurassic. The identification of volcaniclastic layers within these strata is common only within those formations clearly identified as being deposited in the Jurassic (e.g., Bedford Canyon Formation and the volcaniclastic-rich turbidite sequences of central San Diego County). Additionally, a general east to west younging of the strata is indicated for the southern California sequences. That is, the French Valley Formation which contains Early Triassic fossils is east of the Bedford Canyon Formation which is Jurassic and which exhibits an intraformational westward younging (Bajocian on the east to Callovian on the west; Fig. 2). Similarly, the Triassic Julian Schist in eastern San Diego County is east of the volcaniclastic-rich turbidites of central San Diego County, which yield Tithonian fossils. Because of the similarities between all of these formations, we propose that they should be incorporated under a single group herein named the Bedford Canyon Complex. We also believe that these observations unambiguously indicate that the Bedford Canyon Complex were derived from and deposited adjacent to the North American continental margin. Furthermore, the structures and age progressions strongly suggest deformation within the upper levels of an accretionary prism.

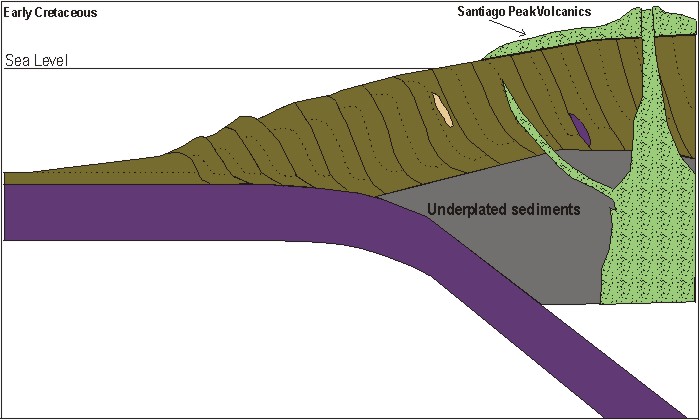

Description of the Santiago Peak Volcanics and associated intrusives (Anderson, 1991; Herzig, 1991; Sutherland, 2002) indicate that the Santiago Peak arc north of the Agua Blanca fault developed atop the Late Triassic through Jurassic Bedford Canyon Complex. Initiation of Early Cretaceous arc magmatism began after the earlier-formed strata were deformed, uplifted, and erosionally beveled as indicated by the truncation of fabrics and structures within the Bedford Canyon Complex at the contact with the overlying volcanics. Evidence supporting a depositional contact between the volcanics and the Bedford Canyon Complex strata, includes a basal conglomerate present along the contact, xenoliths and xenocrysts of Bedford Canyon Complex derivation in the Santiago Peak Volcanics, a pronounced break in deformation across the contact without any indication of shear, and hypabyssal intrusions that cross-cut the turbidites and the contact to feed the overlying volcanics.

![]()

The ancestral Agua Blanca fault:

A non-terminal suture between the Santiago Peak and Alisitos arc segments

Cretaceous arc volcanics yielding primitive “island arc” chemical signatures are observed both north and south of the Agua Blanca fault. However, the details of a number of different data sets do not support the combination of strata and underlying basement from these areas into one tectonic element that evolved as a single entity (e.g., Wetmore et al., 2002, 2004). These data sets indicate that the western part of the Peninsular Ranges is composed of at least two terranes that experienced distinct origins and tectonic evolutions (Wetmore and Paterson, 2003; Wetmore et al., 2004). Wetmore et al., (2004) argue that while the Santiago Peak segment developed as a continental margin arc built on an accretionary prism previously formed at the North American continental margin, the Alisitos arc developed on oceanic lithosphere not previously associated with a continental margin. Detailed study in the region of the Agua Blanca fault reveals the presence of a broad (>15 km wide) fold and thrust belt that is centered upon or tightens against the ancestral Agua Blanca fault, and southwest-vergent ductile shear zone that juxtaposes the Santiago Peak Volcanics with the Alisitos Formation.

Geologic Map of the San Vicente (located in southwest corner)-ancestral Agua Blanca fautl region. Pinks and purples are intrusives, lime green at top is are the Santiago Peak Volcanics, olive green and light green on bottom are volcanic and volcaniclastic-rich Alisitos Fm.

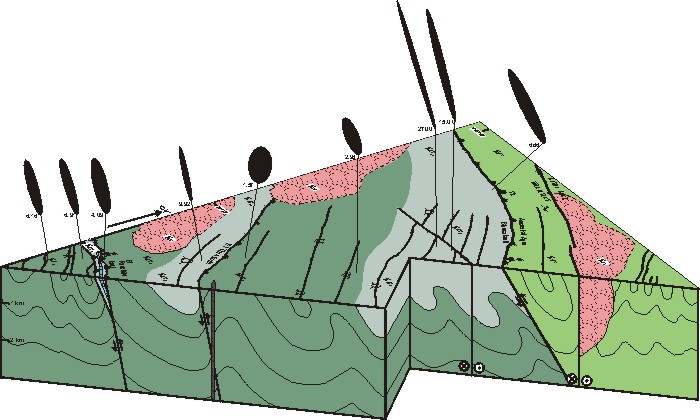

Cross sectional block diagram through the ancestral Agua Blanca fault region. Black ellipses at top are two dimensional XZ-strain ellipses.